Courtney Farren looks comfortable - the sun pouring over her right shoulder through the curtain-drawn windows of her Los Angeles homebase, an organized coffee station situated on the counter over her other shoulder. A sense of peace radiates from my computer screen, manifested from Farren, who is cool and composed on her end of the virtual call. “I love being in LA and I love my space that I have now,” she tells me. “And I love my things. I'm a big ‘thing’ person, like I love my stuff,” she delivers with a little more fervor, joining her hands together like claws as if wanting to assert her possession over her belongings. She doesn’t have much she’s collecting, but what most catches her eye are “like…machines,” she explains broadly and with a laugh, going on to brag about her new sewing machine and a bread maker, which has “changed my life in two days.”

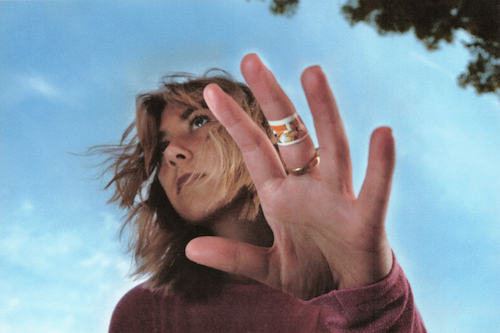

This timeline suggests a transformative span of days for Farren, as just three days prior to our conversation (and apparently just hours before her bread-maker altered her way of being), she released her newest single, “I’m Not Alone (I’m Lonely).” Derisively titled, the song was born out of the contempt she felt being in “a setting where I was like, ‘This is just not exactly me, but I have so much to say about it’...It’s like when you’re in a room and you’re really trying to be yourself, but then just feeling like, ‘Man, I just don’t think this is really who I am.’” It’s a very specific type of isolation that isn’t voluntary and is deliberately different from being alone, as Farren denotes in the track’s name. In distinguishing being lonely from being alone, it's noteworthy to clarify that being lonesome is not inherently tragic, either. Nowhere is this point better illustrated than Farren’s music video for the track, which was shot, edited, and digitized from hi8 tapes by Farren. The footage is populated by candid smiles and moments of small laughter from the artist as she strolls around different scenes, headphones securely fastened to her head. She appears to be the only one who exists in this world, but it's not a sad reality - it’s one she’s come to grips with. “I don’t take anything that seriously, just in my day-to-day,” Farren explains. “I like being happy; I like being a nice person,” she says simply, seemingly freed by her own loneliness and empowered to make her own decisions on how to approach life. Her heavier emotions are reserved for her writing, which has become an outlet to allow for a healthy separation between her daily interactions and her need for expression. “Writing is an expression that’s like, ‘Ok, yeah, I get sad sometimes’...Writing has helped me be able to express some of those emotions. That was something in the music video that I was pairing - almost like, it’s not that serious, and the lyrics sort of say that, too. I grew up kind of feeling like I was a little bit of an outsider, outcast, super self-conscious. (This song) was me speaking to my younger self being like, ‘Well, you’re still kind of weird, but it’s fine. You can let it go. It doesn’t really matter.’”

This profound sense of acceptance is found throughout Farren’s work, but is perhaps most prominent in the videos she creates for her songs. From her perspective, there’s only one trademark quality in her videos: from the disassociated nature of “Care” to the flippant tone of “White Rabbit,” it’s all about letting loose. “I honestly feel like I'm just trying to have a good time,” she says slyly, a half-smile growing as she gives away her secret. “I have a really hard time feeling like I can be myself on the internet. In real life I take a lot of pride in who I’ve become, these feelings about identity - but then on the internet, I get so lost about it, and I think being able to create videos and capture aspects of my personality just by collaborating and doing these kind of DIY things with my friends or just by myself, I can try and have that influence of getting more of my personality into an asset.” While her interest in videography and photography is deep-seeded, it has become a necessary skill as well - not only for her art to grow, but because it is the best use of her resources. “It’s really fun, (but) also it’s challenging because I’m doing everything by myself or enlisting my friends or my partner to do it. But it’s rewarding…Especially with this video, ‘I’m Not Alone (I’m Lonely).’ I had all these grand ideas. I think there’s an element of just practicality, that I’m choosing to do all of this myself. This is where I’m at right now, these are my capabilities with recording and whatever technology comes into play, those things just fall into place.”

While the responsibilities that fall on her shoulders can certainly feel overwhelming at times, would she have it any other way? Farren isn’t so sure - while she sees the value in collaboration, she can’t help but want to feel in charge. When I ask if she likes having a big hand in all things Courtney Farren, she looks at me as if to gauge if I’m being serious or not, before offering a definitive “oh yeah.” She then leans in as if preparing to tell the world’s worst-kept secret: “I love control. That’s a big thing for me…if I shoot all my own photos, I know where they are. I know where they go - they're on my computer and I edit them. If I take 200 photos and I'm like, OK, I like these ten. I know where the other 190 of them are. There's an aspect of that lack of control in some of the artistry that just kind of makes me nervous.” Her anxiety around commanding the direction of her work extends to her writing as well, where she is incredibly “specific” in how she goes about the process.”I get really like obsessive over it being my words, so even collaborating in sessions with producers and stuff…I’m like, ‘I'm writing every word to this song.’ I write pretty quickly and I don't like editing my songs. I'm very stubborn once I've written it - it's hard to change something once it's done for me.” It's safe to assume anything coming from Farren is her own - even her parenthetical title, which she chose as an allusion to the 2000’s. As far as she is concerned, it was her idea first. “I was listening to Arcade Fire a lot, also Gwen Stefani’s “Cool,” and I kind of wanted it to be this sort of throwback, nostalgic 2000’s thing. In 2000, there were all those parentheses, and now all of a sudden everybody's doing it. I feel like the day that the song came out, I saw five other parentheses songs. I was like, the fuck? But anyways, that was my attempt at a throwback, but I guess we're all thinking that.”

While in the driver’s seat, Farren has pushed her music into overdrive in the last year. In April of 2023, she released her EP Rabbit King, which featured four eclectic tracks meant to reflect the diverse emotional conflicts that live within everyone. From flirty melodies (“White Rabbit”) to flittering piano keys of devastation (“Happy”), Farren finds a way to encapsulate the human experience in her intensely-personal writing. In October of last year, Farren returned to drop the first of a string of subsequent singles: first was “I Must Like It,” followed by “Together Together” with featured artist BØRNS, and now “I’m Not Alone (I’m Lonely).” Each track flexes a different muscle for Farren, continuing to build on her varied collection of music to her name. Though they all live together in Farren’s discography, each song she records exists very specifically. “I really try to make my music as like a time capsule of whatever's going on in that time,” Farren details. “And I think a lot of people don't see all the stuff that goes behind a release. They're just like, ‘oh, this song's coming out now? That's what she's going through now.’ I feel like that's tough as an artist because of course you've done it like a year or two years before that - if you're lucky and you're on a good schedule.” The tracks that found their way onto Rabbit King were written just as Farren moved to Los Angeles, and they compared differently to the songs she created before that transition. Aside from the clear emotional connection she has to each song she writes, there is another revealing aspect of Farren’s art that key her into different stages in her life: “‘White Rabbit’ was a marker of that (particular) time in my life…I just look at the length of my hair. I'm like, whoa…in the “King” video, I'm like, I look like a witch. I have like 2 foot long hair. That's insane.” Her most recent singles, however, feel more relevant to the time she finds herself in now, with “I’m Not Alone (I’m Lonely)” representative of a specific scene she had to live through not long ago. “I guess it ended up working out because I like this song, but it was a very uncomfortable moment that brought it out,” she admits, somewhat-joking but mostly earnest.

These kinds of growing pains - rolling with the punches, making the most of a less than ideal situation - seem natural to Farren. She’s had plenty of practice: by the time she was 18, the number of times her family had moved equaled her age. Born in San Francisco, Farren pinballed to new locations and struggled to find a core group of friends. When I ask her how she coped with the constant uprooting in her early life and the significance of stability in her life now, her reaction suggests I just hit her with a ton of bricks. She offers a solemn “damn…” before I apologize for the unexpected weight of the topic. Drudging forward with a more contemplative tone, Farren shares that the constant moving when she was younger felt normal to her, and she even continued the trend when she went out on her own. Beginning with stints in Palm Springs, Vegas, and New York, to name a few, Farren eventually found herself in a remote Croatian village, a retreat that gave her the opportunity to fully invest in her music. Growth, both personal and artistic, is a defining characteristic of that time in her life. “That shaped my ability to feel more secure in who I am right now,” she reflects. “I think I was really searching for something at that time, and I was not finding it. So when I got to LA and had this new sense of freedom out here and had my own place, I really felt like I'd done some serious reworking of who I was, fundamentally.” Farren’s time in Croatia was mostly isolating, far from anyone familiar to her; it was this uniquely distant experience that gave her the perspective necessary to write more broadly. “Before that, I was living in New York and I think a lot of my songs were this kind of confused, young, hopeless romantic, whatever. And now I feel like a lot of my songs are like, what's going on in the world? Am I OK?” It took thousands of miles for Farren to recenter and find her true place, but it seems she’s finally found a home within herself.

If nothing else, Farren’s travels have developed within her a sense of empathy. She’s understanding of the position her parents found themselves in while she was growing up: “They were searching too, and I think there's a lot of things in hindsight now that are a lot easier to deal with because I'm like, ‘man, our parents are just people trying to figure stuff out.’” Being in LA, she’s grateful to be close to family - or, at least most of them. “My brother moved to Florida,” she mentions, resentfully, as she provides me a map of her close ones’ whereabouts. “He needs to move back.”

From what we’ve established so far, there are a few things that seem essential to Courtney Farren’s everyday life: creating things (typically with the assortment of machines she’s gathered), controlling those things she creates, and not taking anything too seriously that may come her way. Fundamental to all of this, she tells me, is hope. “Ohhh man, there's so much to be hopeful for,” Farren says, sincerely and with a glimmer in her voice. ”I'm just really grateful that I have this opportunity to be creating during this time. It's an exceptional privilege and I really don't want to take that for granted. As much as there are difficulties in creating and these barriers, I'm just so grateful to be able to do this and try to put words to things that I need words to. Maybe someone else does too.” The early reception to “I’m Not Alone (I’m Lonely)” has only deepened Farren’s appreciation for the position she’s in. “I'm glad that it's resonating with some people so far. I'm hopeful that that continues. I'm hopeful that I just can continue to be able to create. I'm very happy right now…hope is a very important thing for me and I feel like I have always had that. There's so much to be excited about, and especially in a time where there is a lot of darkness and there's a lot of things that are difficult and people go through. These crazy hardships, but man, people are very resilient and it's definitely admirable. So I have a lot to inspire me.” This is a feat not uncommon to Farren - turning dark into light, struggle into strength, loneliness into freedom. There’s so much more yet to come from the ever-so-hopeful artist - and it most certainly will be done her way.

Sinbad Zaragoza

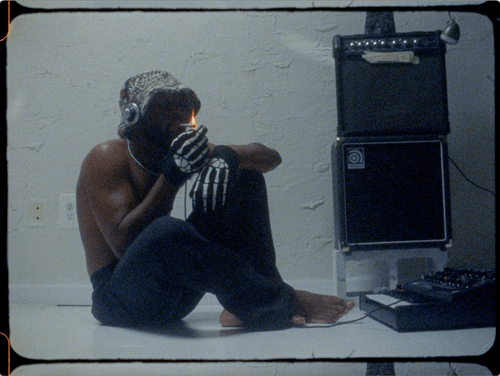

It helps to try and establish an artist’s priorities throughout an interview – whether it be fame, the acclaim, the art, the fans, etc. There was only one thing on Nate Traveller’s mind when he joined our Zoom conversation – chicken wings, with Primal Kitchen buffalo sauce. “Feeling blessed,” he opens, immediately following it up with, “yo, is it fucked up if I eat chicken wings during this?” He gives a thorough recommendation of the sauce, describing its ingredients (avocado oil, dairy-free) and where to find it (Whole Foods), admirably committed to putting me on. The food in front of him isn’t indicative of his priorities, though. His relentless recommendation is perhaps a good tell of what is most important to him: helping others and looking for genuine connection at every opportunity, even (and maybe especially) when there’s a plate full of drums and flats involved.

Through vigorous bites at the wings before him, Nate tells me about the celebration he enjoyed with his team just a few nights ago in accordance with the release of his newest project, Trvll W Friends. On Nate’s sober night out, he was joined by mostly the same crew that helped craft the experiences and subsequent music found on the LP. Trvll W Friends is more of a mission statement than an album title – most of the project was recorded while on the road with a close group of producers, collaborators, and friends, who you can hear on scattered verses and interludes throughout the tracks. The touchpoints of their East Coast trip include Blue Ridge, GA and some spots in New York and New Jersey, the collective making sure to invest themselves in the communities they stopped in.

He shares a story about coming upon a chili fest in one fateful city, and already in our short time speaking, I’ve picked up on Nate’s natural affinity for the concept of serendipity. “We walked around, we tried all the chili,” he tells me. “I got gluten poisoning, but it's all good. I was there with the experience and it was delicious. The chilis were amazing. That part of it, like being able to tap in and like, see the wavelengths of where we're going. These different waves of life and also being able to highlight the local businesses that we resonate with…it's all those moments where it's just like, it really is a faithful moment where you come together, you link up and it blows your mind.” This sentiment is written on Nate permanently and literally, encapsulated in ink on his arm. The Chinese language tattoo he sports is representative of “the relationship by fate or destiny, the binding force between two people,” he explains. “You know, I feel like that's always a sign you're on the right path: when you're getting your mind blown.”

These beyond-coincidence occasions have resulted in some of the most fully-realized tracks of Nate’s recording catalog, uniting for supreme effect on Trvll W Friends. The secret to its genuineness? Full immersion and fearless intentions. “For the most part it was all in this last year…all the songs were made traveling, written and everything,” Nate says, giving specific landmarks for certain tracks where his physical location influenced his melodic direction. “Dead Asleep” came together in Colorado while “Myself Again” originated in Los Angeles, and a number of tracks can be traced back to Nate’s time working with Silk Beats in New York. While imbedding himself into the local scene was essential for Nate, it meant he wouldn’t always be comfortable. He learned to embrace the challenges of a new sound. “The producers bring the best out of me,” he admits. “I tell them like, ‘yo, let's take it to new spaces. Let's do this.’ I always just flow with the production; I'll never be boxed in. Like if someone gives me a hard ass beat and I feel called to it, I'm gonna hit it no matter what it is. And I'm gonna figure out how to fit.”

The box he is fitting himself into lacks the kind of hard and sharp edges most artists find themselves in, and that’s something Nate is looking forward to sharing with fans on his next release. “There's gonna be a lot on this next project I'm working on right now. It's going to be more exploration. People are going to be like, ‘oh, damn’…I've been cutting like Sinatra-type records, bro.” Eager to share his new experimentation, he graciously forwards the track to me. Nate Sinatra is more than a well-conceived adopted identity, it's a reality fans should be preparing for.

While low-register piano ballads aren’t typical of what we’ve come to expect from Nate Traveller, nothing much about his sound has been conformative. His cited influences are wide-ranging, with mentions of The Fray, Flatbush Zombies, Pro Era, and The Underachievers intertwining with his southwest Florida roots. There’s traces of alternative music, pop, hip-hop, and R&B in his music, all genres displayed in varying proportions across his songs. His particular sound can be hard to pin down, but there’s one term Nate has developed that feels fitting: Medicine Pop. “My pops, he told me like, you know what, your music is like medicine, bro. He's like, ‘medicine pop…that should be your genre.’ I really resonate with that cause that's my goal, you know. I want it to be sonically pleasing. I want to hit all those spots sonically, but I also want it to be very medicinal. I want there to be utility to my music. I want it to be useful in a way that goes into the shadow aspect of ourselves as humans, and maybe make someone feel more seen and help them understand. Express something that maybe they felt and they don't know how to articulate it.”

This is a common goal for most artists – to identify a listener’s pain with their lyrics, to pick at hurtful memories like a scab to build a deeper, more permanent connection; to associate themselves through shared pain. While Nate Traveller looks to find the same relation to his listeners, his intention is to facilitate healing, to bring not just relation but understanding. Sometimes that involves “going into those crevices of ourselves where maybe we don't want to be seen or we don't want that part to be open to the world, but still touching on it and being like, ‘hey, this is a human experience, (an) authentic human experience, and we're here to express it.’” The way Nate tells it, his purpose to uplift others comes from his own observations as a music fan. He speaks about how in his formative listening years, “there was a lot of cutting up and punching down on the listener and it still happens a lot in music.” This practice is especially prevalent in hip-hop, a genre that Nate takes obvious influence from. “Hip-hop saved my life. Hip-hop has been such a genre of growth and accountability for me because of the way it cuts up. Like, a good rapper will really put you in perspective and put you in check in a way. But I feel like I just got so tired of hearing the talking down, you know what I'm saying? And so I just really knew, with my music, I want to push up.”

For Nate to continue on this mission, it’s best to stay on the path he’s established for himself. He understands this as well – he plans on making Trvll W Friends an ongoing series, going beyond the sonic and geographical boundaries he’s held so far. “I wanna get out next time,” he tells me excitedly. “Eventually we'll do it outside the country, too.” Some scenes he has his sights on include a B&B in Albuquerque, New Mexico and a ski resort in Colorado. Despite my caution of skiing due to the numerous injuries reported to me by friends, Nate characteristically showed no fear, just awareness of his capabilities. “I feel like I've been pretty athletic all my life, but I don't know,” he says with a laugh. “I'm going to be on the bunny hill, dude. I'm a tiny man, bro. I might end up flying down those hills, you know.” In the face of danger, Nate is willing to sacrifice for the benefit of growth. “Every time I want us to be like breaking out of our shells too and trying new things, you know. Like I want it to be a full on experience like that.”

His tone changes as the conversation shifts to a more humbling topic: Nate’s 2020 diagnosis of Hyperacusis, a condition that reduces his tolerance to noise. He had been mostly chipper and effervescent in our interaction before, but now he takes more time between his words, staring in different directions in search of the right phrases. He gives me a nearly complete timeline of his diagnosis, from the morning he woke up and felt like his ears “could almost break” to the divine intervention he found in plant-based medicine. The purgatory between these events was filled with wrong answers from specialists, leading Nate to online forums that he hoped would uplift his spirits and provide an encouraging community of peers. Instead, he found nothing but pessimism from the few who shared this rare condition with him. “It (was) really depressing,” Nate says of the posts around the forum. “They're like, ‘damn, I've had it for four years; sometimes I feel like I just can't go on anymore…some people are really feeling defeated about it.”

The incurable nature of Hyperacusis can lead many of those diagnosed with it to depression and social isolation, which is exactly what Nate’s doctors looked to treat him for after his diagnosis. When his audiologist recommended antidepressants, Nate cried in his office, beginning to feel the weight of Hyperacusis. He declined the medication but left with a new awareness of the stimulus his ears could take. Talking with others on the phone can hurt his ears due to the frequencies required; if he’s at a restaurant and glasses are clinking for a toast, it can register intensely for Nate. There are times he submits himself to a “sound fast,” and being away from noise can help him build up a tolerance to re-engage socially. “There's so much suffering in that experience,” he admits, honest but not surrendered. “But it's so beautiful,” he immediately continues, “and it's fruitful. There's so much perspective that you get from it.” He committed to continuing music, recording his 2022 LP Born Erased afterward while growing his understanding of the world around him.

Instead of cowering or sheltering himself from the harsh realities of living with Hyperacusis, Nate Traveller has embraced his role as an advocate for all struggling with ear health, and has pointed advice for those unconcerned with threats to their hearing. “If you want to hear the leaves in the trees in the wind when you’re 80 years old or you want to hear your kid cry, you’ve got to take care of your ears,” he warns with care. “I thought I was invincible,” he says of blasting music in his headphones, ignoring his dad’s advice to mind the volume. “Don’t go overboard because it's always going to bite you in the ass. But we do that as humans. I’m so extra – I’m going to be overboard for the rest of my life. So my process is to refine the best I can, but it’s definitely the school of hard knocks.”

The consequences of Hyperacusis on Nate are heightened due to his chosen career as a musician, and he’s come to grips with the fact that there are some aspects of his career he won’t be able to achieve. He doesn’t see himself as a touring artist, as it would be too much of a detriment to his ears. While his perspective has taken the shape of a realist, he does save some room for optimism: he was able to perform a show with one of his friends and collaborators BUNT., offering some hope of occasional live showings for Nate. Chinese medicine has also been a revelation for dealing with the effects of his Hyperacusis, and there’s a possibility of the condition subsiding later in life. “(My acupuncturist) told me that a lot of times it'll come and go, and she believes that it's not going to be with me forever,” Nate says with bated breaths, cautious as if he dables in superstition. But there’s not much reason to believe in these karmic ironies when you have the kind of faith in fate Nate Traveller exudes. “She feels like it's just here, like serving a purpose. And, you know, I hope so. But I'm also not getting lost in that. If this is what it is, I'm a rock this way. And I'm gonna be grateful for what I still do have.”

Moving forward, the conversation was much more grounded, an eye-level appreciation reached between the two of us that made it clear to me how Nate endears himself to fans. He lectures on the music industry and the concentrated nucleus of labels and streaming services, vocalizing his confidence that he can overcome the mafia-like ties because of the support he has and the support he projects. “Never take God out of the equation,” he tells me when discussing the relationships he’s made through music and the impact his songs have had on listeners. When mentioning his work with BUNT., Nate doles out the most candid compliment I’ve ever come across: “BUNT. is such a sweet guy bro…like, you can see his mom in his face.” He muses on the idea of songs living lives of their own, referencing Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” as an example of a song “transforming and taking a whole new form.” His collaboration with BUNT. on 2023 release “Clouds” placed Nate in a position where he was looked favorably upon by the powers-that-be in the industry, his streaming numbers skyrocketing and fanbase multiplying. The sudden success hasn’t seemed to derail his approach whatsoever – “Always just understand that this higher power could just come in and blow your mind in the best way possible. You know what I'm saying? And never write that off or count that out.”

While his career actively unfolds in front of him, he still has goals he hopes of achieving sooner rather than later, including becoming a more visible advocate for ear health. “I would love to get endorsed by Eargasm. I would love to be pushed more in the forefront, I would love to be on a commercial,” Nates expresses passionately, his enthusiasm for the cause overwhelming any doubts of insincerity. In regards to his music, Nate would like to curate an official Medicine Pop playlist on a streaming service, highlighting the voices who provide the same spiritual cures as he does. Finally, we decide to begin a movement to nationalize Nate Traveller Day, an occasion created by his father: “Every Friday is Nate Traveller Day,” Nate shares, brimming with pride. “He plays my music for all his work friends.” As the Zoom window closes and I scroll the market for Primal Kitchen buffalo sauce, I take a moment to consider the nuanced but abrupt impact of Nate Traveller that has already taken place. While my instinct is to attribute our connection to good fortune, I’m only reminded of Nate’s strict no-accident attitude. “When the magnets come together, it's always for a reason, you know?” he assured me early in the interview. “It's always for a purpose.” Given his fateful journey to becoming a voice for millions to hold on to, it's hard to cast any doubts.

I’m catching Aimee Vant at a good time – the night before, she performed a backyard concert where the intimate setting allowed for casual conversation during the set. It’s her favorite type of show to play, and the support from those in the audience feels more meaningful to Vant now more than ever: today she releases her first song as an independent artist in some time. Early returns are good for Vant on the new track: “A lot of people were coming up after and saying they were excited for it, which felt really good,” she tells me over Zoom, her excitement palpable yet disguised by a calm, focused demeanor.

New music and fan support aside, it’s not always a good time for Aimee Vant. This is abundantly clear if you’ve ever come across one of her pain-tinged, blue-hued recordings (“I feel ten out of ten / Like zero percent of the time,” she muses on previous single “Trash”), but even more obvious when you consider her precarious position as it relates to her age. “Everything feels a little too precious and a little too high stakes when you're in your mid-20’s,” she explains, trying to answer to the dread and self-deprecation that can often take center stage in her songs. “It's just such an uncertain time where some people are doing really well and some people are on the opposite end of the spectrum where everything's unknown. You don't have your roots anywhere. And I think it just makes it so every decision you make feels like life or death and I carry a lot of stress in the fact that every day feels like a ticking time clock to reach my goals faster. I feel like things have to be better by next year or tomorrow.”

Vant’s sentiment about her place in life is shared across her generation, an anxiety that is compounded by the still-rippling effects of a pandemic. The timing was doubly troublesome for Vant, as she was still in the midst of identifying herself as an artist when things slowed down and got lonely. For as stagnating or regressive as the pandemic was for most artists, the time in isolation was somewhat revelatory for Vant. “It kind of honed something that I didn't realize I was digging into, which is that a lot of my favorite artists, the music they make is very, very personal and it almost sounds like they're making it just for themselves,” she shares. “Like they're just in their bedroom making it…basically, it's just like saying their problems away.” Spending so much time within four walls funneled Vant to do the same, therapizing through her writings and suddenly finding herself headed in the right direction.

Though confident she was on the right path as an artist, Vant has had to navigate the winding roads music often leads us down, listeners and performers alike. While at her core she is a singer-songwriter who could find her way through any stripped, acoustic setting, Vant has wandered from her indie instincts in favor of the allure presented by explosive, dramatic pop music. This sound can be more about balance than utility, as she’s aware of how melancholy her lyrics can come across and sees this brand of production as a way to make amends for the “lyrical uncertainty” common in her songs. As far as which sound she gravitates to more, it’s less of a science to Vant as it is a natural pull to one or the other: “Especially lately, I’ve been making peace with the fact that I can let the tides take me in either direction at any time.”

No matter the sound of Vant’s music, the tone of the music is typically consistent – that being self-critical, insecure, overwhelmed and generally disappointed. When I pushed on why she gravitates so much towards these themes, I was relieved to learn that there isn’t a dark cloud perpetually following Vant in her journeys. Her mentor Kara Dioguardi tells Vant often how positive of a person she is, making the helplessness heard in her music difficult to comprehend at times. “But I said to her, that's the part that I have to get out when I write,” Vant says of the negativity in her work. “So that's the part that ends up getting funneled into my music. I think the most therapeutic part of songwriting is taking an ugly feeling and making it a piece of work that you're proud of.” When she stumbles upon happiness, she doesn’t have the desire to write about it – she’d rather live in the moment, acutely aware of the fleeting nature of life’s pleasures. Writing about her problems is a way to “get them out” of her consciousness, a practice that provides instant relief and clears the way for the better days to come.

“Life or Death,” Vant’s new song set to arrive on November 17th, is in no way a departure from Vant’s core musical principles. The track wouldn’t sound out of place on her latest EP, Trash, but also feels like a natural evolution, the next logical step for Vant to take towards realizing her artistic vision. “Life or Death” isn’t as crunchy as 2022’s “SAFEWORD” or as echoing as prior single “Voicemail,” but encompasses elements of seemingly every release she’s shared to this point. Assuredly sincere and boldly vulnerable, the writing on “Life or Death” mirrors the all-cards-on-the-table approach Vant has endeared herself to. Strains of her idols are recognizable in the lyrics; while she’s noted Gracie Abrams and Holly Humberstone as inspirations of hers due to their willingness to say the private things on record, Vant packs more of a punch in her delivery and production, far less apologetic for any of the sentiments she shares in her songs.

While the direction of “Life or Death” may have been fairly logical, the intimidating aspect of this release for Vant may come in the fact that it is her first independent release in some time. While grateful for the team and supporters who have contributed to her success to this point, it was time for Vant to prioritize her own ideas for how her music should sound, look, and feel. Her focus before was on pleasing those around her; now, the only one left to impress is herself. “I think I wasn't able to focus on what I want to do and what I want to sound like and what I want my career to look like,” she says of the experience of working with a team. “So I think now I've gotten to this point that I feel really good about the only voice I'm really following is the one in my head. I feel really excited to put music out, more than I have in a while, so it feels really, really good.” While she’s quick to share her satisfaction with me, I’ve learned not to expect to be hearing about it in a song anytime soon.

This isn’t to say we’ll never hear a raucous, rapturous anthem from Vant – we may in fact get a high-spirited song from her, but it may not be her voice featured on such a track. She’s been donating a lot of lyrics to other artists, collaborating in writing sessions with artists that embrace her as she is. When she found herself in rooms trying to write pop songs, Vant often felt those around her were trying to “kind of wash away all the quirkiness of my writing.” With a central feature to any Vant song being the “cheeky” lyricism and delivery on behalf of Vant herself, she looked towards other artists who were encouraging Vant to use her voice as she knows best. This includes leaning into specifics in some aspects of her writing, which she says has broken down some emotional barriers she was otherwise hesitant to approach. “The songs that you're most afraid to write are the songs that you have to write the most,” Vant says, quoting a philosophy she often reminds herself of. “I think in that sense that's what has led me to still just be brutally honest, and I think that's the music I hold closest to me, even though it's scary.”

The release of “Life or Death” is just the beginning of what Vant has planned for herself. Her next goal is to hit the road on a tour, either opening or headlining some gigs beyond her preferred backyard sessions. And an impromptu announcement: she’s looking to release an album soon. “I just decided last week, I was just looking through my catalog,” she tells me, the surprise on my face mirrored on hers. Mainly produced and written by Vant, there’s no question listeners will get her in full-form whenever the LP arrives. That likely means she’ll be diving into specifics, which Vant has never shied away from in the past. When I ask if she thinks any of the song’s subjects know they are a target within a track, she considers it for a moment. “That's a really good question,” she tells me, a compliment I’m glad to receive from a question so invasive. “They probably know,” she concedes, a look of apathy resting on her face. “As long as I'm not name dropping or anything, I feel like I am able to do it…I don't know if they're listening, but they probably would know if they listened.” If they’re not tuned into the vindicating, cathartic, sheepishly melancholy, sing-slash-scream-along’s of Aimee Vant, they likely ought to be, just as is true for the rest of us.

For the chronically online, the bored-scrollers, and the sporadic users alike, an unofficial community guideline for TikTok is that judgment be suspended when you open the app. In a place with unpredictable content and an untrustworthy algorithm, one’s feed is not a fair representation of their character. And before you hold content creators to a different standard, please take into account those who live on the apps out of necessity. Specifically keep in mindPIAO, who’s posts on these platforms are meant for a specific audience. “I'm constantly telling my friends or the people that know me personally: no, don't look at my TikTok!” she pleads with me over Zoom, jetlagged yet persevering to assure she gets her message across. “Like, TikTok is for people who don't know me. Do not go on my TikTok!”

As much as she begs for those close to her to stay away, social media has been one of the only places to keep up with PIAO in the past year since the release of her debut EP, Tissues. The project was a landmark moment for the Shanghai-born, Canada-raised artist who made a strong impression in the 5 songs comprising the EP. Whether it was soaring vocals, snappy melodies, or heartfelt ballads, PIAO proved to be a talent that belonged in the pop space. After publishing the songs that encapsulated her experience throughout COVID and being a young songwriter, she deservedly took a break, and kindly kept fans in the loop with occasional posts to her social accounts. It’s still a work in progress, she admits, as the act of self-promotion doesn’t seem to hit the right note for the always-on-key singer. “You know how people recreate scenes (on TikTok) where it's like, they bump into a stranger, and then, ‘Oh my god, I think I listened to your music!’ I could not get myself to do that,” PIAO says, second-hand embarrassedly. Instead, her posts are candid looks into her personal interests, capsules from a time in her life, and kind reminders that, yes, new music is coming soon.

In a time where it has become popular and convenient to categorize periods of our lives as eras, PIAO is beginning a new one with her most recent releases. Returning in September with the raucous single “Cardcaptor,” she’s doubling-down on her new sound with “Neopet,” out today. The bombastic and brash production of “Neopet” sets the tone for the state of mind PIAO finds herself in creatively, to which she applies a very inconspicuous adjective. “After 'Tissues,' we were like, ‘what do we want to do next?’” she tells me. “I was like, I definitely don’t want to be in the Tissues era. I remember just saying, ‘I think I wanna make cursed music,’” she says with a laugh. What is cursed music, asked her team, preempting my curiosity as well. “I don’t know, just music that sounds kind of cursed,” PIAO answers, vaguely but acutely defined in the resulting music. “I’m feeling like fuck it, let’s just go.”

The genesis of these songs as cursed isn’t meant to imply they’re inherently evil; in fact, much of the inspiration for both “Cardcaptor” and “Neopet” come from a source of joy and innocence for PIAO. Following the release of Tissues, she was left to reflect on her life, on not only how far she had come but what had gotten her to this place. “I was thinking about the stuff that makes me really, truly happy. And Neopets was one of the things that made me truly happy. Watching Cardcaptor (Sakura, a Japanese manga series), I was so happy doing that as a child,” she reminisces, ripe with sentiment. But when you’re making cursed music, you inevitably end up asking yourself the ultimate question: “We were like, ‘how can we make this more cursed than it is?’” After some pitched vocals and production tricks, “Neopet” arrives fully-formed, not quite defining but solidifying an era PIAO is ready to embrace.

No matter how PIAO chooses to describe her music, “cursed” isn’t a satisfactory label for music to be released through. So, for both “Cardcaptor” and “Neopet,” PIAO chose to classify them as K-Pop, a genre she never thought she would have entertained. “I used to be a K-pop hater in high school,” she shares. “Probably because I wanted to be different, not because I actually hated it, I think. I must have had a phase.” As far as teenage rebellions go, PIAO’s was pretty mild, and certainly not irreversible. Growing her affinity for the genre as a fan of BLACKPINK, she suddenly felt entrenched in the “big world” of K-Pop, the “earcandy and eye candy” that fuels the music, which coincidentally became a muse for her own recordings. “I let myself fall into it and let it influence me creatively,” she says, as is evidenced by how free and comfortable she sounds in her recent contributions to the genre. But in the end, she tells me, the music is all the same, no matter whatever label is conveniently placed on a song’s packaging. Rather than being restrained to one genre, PIAO thinks of her songs as nondescript reflections of herself: “I think my music reflects how I am in real life, which is indecisive,” she laughs. There’s little intention when it comes to a song’s structure, instead placing priority on the emotion she’s trying to convey. One day, she hopes, she’ll be able to write for other artists. But for now, she’s finding her place in her own shoes, while making sarcastic promises that she’ll “have a normal song one day.”

While the allure of K-Pop didn’t fit her social status in high school, there was a budding sensation she couldn’t help but feel inspired by. “Somebody showed me a video of Rich Brian and I was just like, ‘what in the world is this Asian boy doing?’” she recalls, instantly curious and transfixed by the artist’s momentum. Further investigation unearthed the existence of 88rising, a hybrid management, record label, and marketing company that was showcasing the talent of Asian-Americans and Asian artists working in Western industries. Aside from her initial interest, PIAO didn’t invest much attention into the collective. She had other priorities – “I was actually a full-on business nerd in high school” – and had plans to attend a dream school of hers to study finance. In a moment of inspiration and with nothing to lose, she signed up for an audition at Berklee College of Music. Aside from her childhood dream of being a musician, there was one other clear draw for PIAO to attend Berklee: “they didn’t require an SAT score, and I’m Canadian and we don’t do SAT’s,” she admits. Fatefully enough, PIAO was offered a full-ride to attend Berklee, throwing a wrench into her plans to attend business school. Ultimately, it was an anecdote from her mother, who is also a singer, that pushed her towards attending Berklee. Since she was as young as seven years old, PIAO would sing in her room and dream of being an artist. Try as her mother could to temper PIAO’s expectations, often reminding her of the lack of Asian stars in music, PIAO couldn’t resist the allure of being an artist. “I’m not a religious person, but I feel like there was a big universal push for me (to pursue music). Literally everything in its power and its matter is pushing me to do this thing which I think I was just scared to do,” she says, recalling what compelled her to pursue music.

A few weeks after “Cardcaptor’s" release this year, PIAO signed a publishing deal with 88rising, a moment that feels as full-circle for PIAO as it does validating. “(When) I first heard about 88rising, (I was) almost fearful of how courageous their initial ambition was because I didn’t have that ambition myself. I was like, ‘Oh my God, how are they so certain that this will work?’...It feels like I’ve been accepted into this little community…It's been a long time coming.”

Near the end of our conversation, PIAO must apologize: her alarm just went off, one she set to wake her up from her aforementioned jetlagged haze. She’s just returned a few days ago from a month long trip to China and a stint in Japan, and is still trying to get back up to speed. “I definitely am experiencing, like, post-vacation sadness,” she confesses, longing for the place she just left and mournful of the rest she cannot get. She can appreciate the perspective gained from the trip, a pivotal experience for PIAO to reconnect with her community, culture, and family. “It definitely was not just like a woo-hoo trip, but I think it was needed,” she concludes. And it's not as if PIAO had nothing to return to: upon the week of her return to the States, “Neopet” is officially out today and she is scheduled to play her very own showcase at the Winston House in Los Angeles. While her performance at KCon in LA earlier in the year has her primed for her big night, she most looks forward to relishing the simple tenants of live music: “I’m looking forward to seeing people, taking my time, and having fun,” she says, as energized talking about the show as she has been in our entire meeting. After a month away and a showcase to return to, along with new music in tow, it must feel good to be back. Fans of PIAO can likely relate, as their anticipation is just as intense and even longer awaited. As if she ever could, PIAO surely won’t disappoint.

This year was a doozy. In the end, I take away what it took to get through it. From the angry to the soothing to the crushing to the comforting, here's the sounds that carried me through.

Honorable Mentions:

PinkPantheress, Heaven knows - A riveting album where each song possesses moments that can feel cinematic or evolutionary, with incredible highs and lows that don't lag too far behind (or for very long).

Earl Sweatshirt & The Alchemist, VOIR DIRE - One of rap's most in-shape and rigorous rhymers is in the zone, and knows just who to call to bring out his best.

Feist, Multitudes - In a state of meditation, Feist pens some of the most complex and forth-right writing you could find this year.

Veeze, Ganger - I will point you to "Rich No Duh" and forfeit the rest of my words here, thanks.

Alan Palomo, World Of Hassle - A three-dimensional soundscape that brings a different but equally interesting thrill with each song.

Olivia Rodrigo, GUTS - A real good laugh at the idea of a sophomore slump from one of the more impressive pop songwriters in recent memory.

Ragz Originale, BARE SUGAR - A sonic flood of confidence and personality, BARE SUGAR was neglected as one of the year’s most cohesive listens in the hip-hop/R&B arena.

The Japanese House, In The End It Always Does - A very considered songwriter and musician, Amber Bain is quietly observant with moments of overwhelming earnestness.

Anna St. Louis, In The Air - I wish I could feel the way this album sounds all the time - an eternal state of "Trace" would do me well.

Larry June & The Alchemist, The Great Escape - Between the two, being supremely cool and talented never sounded so easy.

Olivia Dean, Messy

The title of Olivia Dean's debut LP is deceiving to how pristine all aspects of the album are presented. She endears herself to the listener with each track on Messy: her careful writing, pull-you-in-a-little-closer voice, the frequent flares that compliment the moments of contemplative narrative. And it bears repeating, her voice - it's a voice that is hard to imagine feeling out of place anywhere, though it's best suited around pianos and live instrumentation; it's not fragile, it's gentle; it's not strong, it's alluring. She has the kind of voice (and personality to boot) that is deserving of a Boiler Room residency. It's evident that Dean finds great joy and pride in her music, determined to make the most of her talent with every performance. While a more straight-forward pop approach was likely in the cards, Messy feels like a pure-hearted attempt to continue to curate Dean's artistic repertoire. Unrestricted, it feels like she has room to breathe throughout the record; she takes ownership of each track in a way uncommon of most pop artists today. All of these ideals come to a head on the celebratory "Carmen" - while not quite a victory lap for herself, Dean's joyous recognition of where she's come from and where she's headed inspires even the most passive ears. It's nothing short of a pleasure to see her work unfold on Messy.

Jordan Ward, moreward (FORWARD)

An odds-friendly favorite for Rookie of the Year, St Louis's Jordan Ward rose to fan-favorite status by making no compromises. Not conventional but also not necessarily innovative, Ward seems to have created a new variant of modern hip-hop/R&B artists. While genre classification is an argument to be had, I side with Ward as a hip-hop voice, not with the motive of diminishing the breadth of R&B but rather as a boast of rap's ability to leak and find itself puddled in a way that reflects other genres as much as itself. Brimming with charisma and a well-to-do approach, moreward (FORWARD) is light on its feet, moving at Ward's gliding pace without missing a beat. This particular title serves as the deluxe to initial release FORWARD, including bonus tracks from 6lack and Easton Fitz that continue to propel Ward's momentum. Soulful and grounded, moreward (FORWARD) has an elastic quality to not only its sound but its identity, practically ensuring the album to withstand the shape-shifting trends of the genre. In a year where rap lost some of its luster near the top, moreward (FORWARD) slots in as one of the year's premier rap albums.

Squirrel Flower, Tomorrow's Fire

At once contemplative and immediate, Tomorrow's Fire is as definitive of an album as you could find this year. Ella Williams has a firm grip on each track on the record, never deviating or losing focus in what plays as an utterly immersive 10-track collection. "Alley Light" holds an air of romance that is overshadowed by the stark darkness heard in the guitars echoing throughout; "Canyon" feels as vast as its title suggests, with Williams emphatically poetic in her performance; finale "Finally Rain" is off-handedly tender, similar in ilk to prior tracks but with a lifting of a weight otherwise present throughout. The writing and sound of Tomorrow's Fire is an incredible snapshot into the position Squirrel Flower finds herself now - potential be damned, she exists most prominently in the present.

Blondshell, Blondshell (Deluxe Edition)

Sabrina Teitelbaum, the 26-year-old artist native to LA, has a great voice. In the past, it has lent itself towards more pop-focused recordings, throwing its weight around with more vibrancy and enthusiasm. Her voice as Blondshell is even better - though her voice, in this instance, is in reference to her writing style rather than her performance. It's her dry, self-effacing sense of humor, sarcasm, turning of a phrase, and nail-on-the-head descriptors that establish Blondshell as a character and a vessel. In the doom and gloom of tracks like "Olympus" and "It Wasn't Love," you can almost hear the bags under her eyes, the chip on her shoulder, the dark cloud looming over her head.

When I wrote about this album at the halfway point of the year, I called Blondshell more of a cautionary tale for those in their 20's than a scared-straight testimony. The bonus tracks that arrived with the deluxe release of the album in July serve as an epilogue of sorts: "It Wasn't Love" is a mostly-sober reflection of a relationship that could have easily served as inspiration for original releases "Joiner" or "Kiss City"; "Street Rat" and "Cartoon Earthquake" mimic the beyond-self awareness that plagues the writing of earlier songs; "Tarmac 2" and "Kiss City (home demo)" re-frame the album in a way that plainly reveals Blondshell's insecurities - with no guitars or drums to mask emotions, it's as bare as we've seen her so far. While her vulnerability persists throughout the record, it's on these two re-imagined versions where Blondshell lets her guard down for good. To hear her sing the chorus of "Tarmac" - "Everything revolves around kissing and / When he's here / I'm alone" - in this bare-bones setting makes you painfully conscious of her feeling, as if you can feel the delicate gravitational pull of this orbit she's fallen victim to. Whether it's the devastating, knock-out punch one-liners littered throughout the tracklist or the nostalgically-appropriate grunge influences, Blondshell delivers some of the most exhilarating musical moments of the year on her not soon to be forgotten debut.

Del Water Gap, I Miss You Already + I Haven't Even Left Yet

The chief critique (at least personally) surrounding Del Water Gap, the solo project of Samuel Holden Jaffe, as an artist is fair - he is derivative of his influences to a fault. I have framed him privately as a sort of toothless-The 1975: not quite as daring as lead man Matty Healy but just as self-serious. A quality the two share that makes them both successful in their varying degrees of ego is a commitment to the bit, so to say. There's few instances of Jaffe putting himself in the other's shoes on this album, and while centering one's self isn't necessarily a sin, it opposes Jaffe's perception of himself. This flaw is certainly not fatal to his craft, as the songs on I Miss You Already + I Haven't Left Yet (I mean, the title pretty much makes my point for me!) are overwhelmingly beguiling, with Jaffe's character casted as dangerous enough to be advised against but innocent enough to insinuate you won't be hurt too bad. For the track's of IMYA+IHLY to persevere through Jaffe's character flaws is a feat of itself, and makes it one of the more curiously satisfying albums of the year.

Blonde Redhead, Sit Down For Dinner

On their first album in 9 years, Blonde Redhead mesmerizes more than anything on their transcendent release Sit Down For Dinner. Keeping in tradition with their shoegaze roots, the atmosphere of the record can envelop you to a point you neglect the poignant writing scattered throughout. "Have you seen, have you heard of a love that has no crime?" goes the final words of lead track "Snowman," properly setting the table for the emotional demolition in tow. The effective climax of the album comes in it's two-part title track, drawn from a phrase authored by Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking. "I know you're tired of living / But the dying is not so easy," begins vocalist Kazu Makino, but the real blow is yet to come: "But for some, it comes in an instant / You sit down for dinner / And the life as you know it ends / No pity," the final words a devastating gut punch given all the track's circumstances. Though serviceable as ambiance music, Sit Down For Dinner transforms when given the proper investment; you'd be hard-pressed to find many more albums that are harder to swallow emotionally than Blonde Redhead's latest.

Ryan Beatty, Calico

Throughout Calico, Ryan Beatty meets you at your most intimate moments, memories, and thoughts. From the curious weight of the piano that introduces “Ribbons” to the hollow guitar of “Little Faith,” Beatty meets the music with all he has. His incessant pleas to “have a little faith” on the album’s closing track only reinforce the painful memories recounted on those that came before, the cruel savior that is hope blossoming before him. Swallow your pride as you dutifully serve your fate, he seems to be saying. Elsewhere, he is overwhelmingly endearing in his songwriting - single "White Teeth" pierces the skin with its pointed sensibility. Across the record, Beatty is fragile but not brittle; there are moments where the song takes the form of a hymn, not necessarily in structure but in religious divinity. Listen, if you will, to the character of the guitar strings of "Bruises Off The Peach," or the rich textures in Beatty's voice on "Cinnamon Bread." Calico sounds like the best kind of friend, the one you share the longest history and most sincere bond with. A shoulder to lean on and a hand to hold, Beatty’s third album reminds us why we listen in the first place.

Jess Williamson, Time Ain't Accidental

Likely the top contributor to curbing my cynicism around country music, Time Ain't Accidental is eye-opening on a couple fronts. For its author, its an unashamedly personal account of love and self-discovery, not claiming to be anything more than Williamson's heartfelt tragedies she's come to accept as treasures. There's an absurd amount of faith baked into the album - as is suggested in its title - that is truly contagious, whether that be a symptom of Williamson's transparent lyrics and vocals or the banjo that treads optimistically throughout. "The difference between us is when I sing it, I really mean it," she spews at a past love on "Chasing Spirits," her words delivered bravely and with contempt. It's a beautiful trick that Williamson is able to pull off in making the personal feel universal, telling her own stories for the listener to hear them as their own. You get the feeling that while singing her heart out, Williamson is staring into the horizon beyond, the sun certainly rising rather than setting.

Zach Bryan, Zach Bryan

“I have this weird fear of like, if I don’t put this music out, someone 20 years from now isn’t going to be able to hear it," Zach Bryan told the New York Times in 2022, attempting to explain the sheer volume of music he's released in recent years, best encapsulated by the 34-track album American Heartbreak. "If some kid needs this in 40 years and he’s 16, he’s sitting in his room, what if I didn’t put out ‘Quiet, Heavy Dreams’? What if that’s his favorite song of all time?” From this quote grew a share of understanding between myself and Bryan, who I was actively disinterested in prior to reading the profile. It was more arrogance than ignorance that encouraged me to deflect his work, but in finally giving him a prejudice-free listen with the release of his self-titled album this year, I was able to appreciate his inherent emotionality, and dedication to the craft. His insecurities may have gotten the best of him again, as the album is perhaps bloated in some aspects, but his intentions are true. It's hard to walk away from tracks like "Ticking" and "Jake's Piano - Long Island" and not feel more attached to Bryan. Maybe the biggest compliment you can give to an artist is to admit their audience is well-earned; Zach Bryan survives on its merit, deserving of every listen.

Bakar, Halo

A curious case given his sudden and somewhat odd rise to notoriety, Bakar writes off the "one hit wonder" title with Halo. There are ceremonious highs on the album, as Bakar's simple but effective writing is bolstered by his uncanny knack for melody. After catching ears with "Hell N Back," he became an artist who burrows, further ingraining his voice and off-kilter alt-pop with the likes of "Facts_Situations," "Right Here, For Now," and "I'm Done," among others. On the topic of "Hell N Back," which peaked at number 1 on several international charts, Bakar reinforces the track with a Summer Walker feature on the album, an equally surprising and effective choice that proves Bakar's eptitude when it comes to finding the right fit for him. When it mattered the most, Bakar stuck to his guns, and he's rewarded with one of the year's most inspiring albums.

Mitski, The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We

I went into this Mitski album blind, ashamedly oblivious to her past work, mostly on account of my own negligence. Still, in this unfamiliarity, The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We felt like being held by a familiar silhouette. Her embrace is empathetic, snug and welcomed, measured and natural. Belying the virality of "My Love Mine All Mine" are equally delicate tracks that revel in the burden of herself, namely "I Don't Like My Mind," "When Memories Snow," and "The Deal." Yet still there are moments that rest adjacently to the affairs of "My Love Mine All Mine": the metaphor that drives "I'm Your Man" sits comfortably among some of Mitski's most devastating writing to date, while the light pours in on the helplessly romantic "Heaven." While it's 32 minute runtime may feel brisk, TLIIASAW is damp with the condensation of Mitski's vulnerabilities, an exhaustive listen that continues to insist upon it's listener to press play once more and feel it all again, at full force.

Indigo De Souza, All of This Will End

The way Indigo De Souza captures the human condition is apparent in the title of her standout album from April of this year: she approaches the topic with candor, oscillating fluidly in her attitude towards her surroundings. Her voice creates an ambiguity that is enthralling - her quick-draw breaths and liberated expression leave room for interpretation. It's often difficult to decipher if she is on the brink of laughing or crying. The best example of this dichotomy comes on "You Can Be Mean," where Indigo gives permission for her object of affection to mistreat her: "You can be a dick to me / It's what I'm used to," she bellows, drawing out the final lyric and releasing it wildly. While her voice is seemingly tinged with humor, you wonder if she's in on the joke only for the added benefit of self-depreciation. At other times, her anxieties are presented genuinely: "Parking Lot" is an enlivened account of enduring a crisis at the grocery store, while "Younger and Dumber" closes the album on the note of a ballad, stripping away all facades and room for interpretation as Indigo shares clear-eyed reflections without reaching answers indicative of closure. This is life as we know it, as Indigo is supremely aware: "I don't have answers, no one does / I've been finding comfort in that."

Wednesday, Rat Saw God

Let's hear it for the outsiders! The Asheville, North Carolina outfit reaps praise on their most expansive, deliberate statement yet in Rat Saw God. The raucous electricity of the album left me paralyzed upon early listens, head spinning and internal compass gone awry. Once I got my wits about me, there was little I could do to shake it - the gothic pageantry of the music measures in at epic, perhaps no more evident than on the rustic "Bull Believer," with a finish you have to hear to believe. And still there are moments that verge on tender, namely "Formula One" and "Chosen to Deserve," the latter so genuine in its intent you may not realize the horrors at play. And these horrors are hard to ignore - or, rather, resist, given how compellingly they're delivered. Across Rat Saw God, Karly Hartzman and the crew give their all to prove their lyrics true: "Nothing will ever be as vivid as the darkest time of my life," the lead singer drawls on "What's So Funny," continuing, "Suddenly it's a tragic story / But that's what's so funny." Holding together the whole of the album is a sense of serenity, as is captured in the record's final scene: a TV in the gas pump, blaring into the dark, not giving a damn who is there to listen.

Caroline Polachek, Desire, I Want To Turn Into You

For my money the most fully-formed album of the year, Caroline Polachek's magnum opus is pedal-to-the-metal from its opening moments. Her howling to open Desire, I Want To Turn Into You boldly announces her presence, and she is only more firmly imprinted on the tracks to come. To commentate on this album is mostly about how it makes the listener feel: it feels victorious, rapturous, awakened, alive. Polachek shape-shifts, metamorphosizes, and all-around dazzles with each passing second - for all there seems there is to say about Desire, words cannot do the justice afforded by a listen. To list the collection of genres at play seems obsolete considering their application; genre is at Polachek's discretion to fit into her style, not the other way around. An absolute apex of an album, Desire and all of its forms transcend the here and now.

Samia, Honey

In an interview earlier this year, friend and admirer Blondshell offered a quote on what she appreciates most about Samia's music: "In (Samia's) writing, she sees a lot of beauty around her and she writes about it so specifically." It's a pointed compliment that is well-paid, a truth that speaks best to the most redeeming qualities of Samia's work. Honey almost plays more like a novel than an album, weaving a narrative together somewhat disjointedly but to profound results. The album is unpredictably fun at times, namely on tracks "Charm You" and "Honey," which also sets the listener up for quite the whiplash in transitioning musically and emotionally from "Breathing Song" to the aforementioned titular track. A whole-hearted exploration of Samia's conscience, its appropriate to feel invasive as a listener at times. In the end, it's for everyone's benefit to have been on this journey Samia calls Honey; after getting past these insecurities, we hope to take Samia at her own words, "To me, it was a good time."

feeble little horse, Girl with Fish

It's hard to know where to begin with feeble little horse. From track one on, the Pittsburgh band maintains a nonchalant ease that somehow finds its way to charisma. "I know you want me, freak," goes the opening line of the album; "Your smile's like lines in the concrete," vocalist Lydia Slocum deadpans later on, in her monotonous delivery that is her standard. A notable exception to Slocum's indifferent tone comes on the twiddle-y "Heaven," who's sudden turn to guitar uprising midway through the song hits a nerve for Slocum that provides Girl with Fish's most dynamic moment - if you weren't listening closely enough before, she's demanding you hear her now. Don't let her seemingly unenthusiastic approach fool you, as the writing is on par with the year's best and sustained across all tracks. The album is lean but muscular when it comes down to it - the band isn't afraid to flex and get gritty if need be. Despite rumors of contentions amid members, the group has uncanny chemistry and complimentary visions that make Girl with Fish hard to take off repeat.

MJ Lenderman, And the Wind (Live and Loose!)

I wrote about MJ Lenderman's Boat Songs on last year's music list, and while most of the tracks on that album appear again on his live recording And The Wind (Live and Loose!), the songs in this context usurp their prior release. The live album as a whole arrives as the perfect medium for Lenderman's traits as an artist to shine through: his rugged voice has an anatomy to it, and you can hear how pointed his elbows and joints are; his voice is lanky and his writing is wiry. It's incredible to me how much more I have to say about this music that I've been listening to for over a year, but in this instance, I'll take advice from Lenderman himself: “The less people hear me talk, the more they can project on me or think I’m a smart guy.”

Rory, I Thought It'd Be Different

The passion project of producer and professional entertainer Rory proves worth the wait - the cast of voices and personalities on his debut album are the product of well-considered curation, a steadfast belief in concept that pays dividends. Whether unheralded talent like Aáyanna and Hablot Brown or proven commodities the likes of James Fauntleroy and Ari Lennox, Rory knows just the right setting to facilitate excellence. I Thought It'd Be Different is much more than the sum of it's plentiful, complimentary parts, a cozy album that leaves more proven than doubted. For any that know Rory's story, you wouldn't envision it being any different.

boygenius, the record

A bit overwhelmed with the amount of coverage boygenius collected around their release and perhaps more intimidated by the comprehensive criticism around the music, I chose a more unconventional medium to review the record earlier this year. Revisiting months later, their star rising even more than it had during their avalanche in March, it's hard to mention the year in music and omit boygenius. Their prominence is merit-based as much as it is idea-based - sure, a supergroup of trend-bucking singer-songwriters firm in their sense of group sounds cool, but it's another thing for the music to serve as proof of concept. There's strength, there's range, there's solemn devastation, and there's unconditional commitment embedded into the record; even in it's widespread acclaim, there doesn't seem enough words to express the album's brilliance.

100 gecs, 10,000 gecs

Contrary to popular belief among unsuspecting patrons I've shared the work of 100 gecs with, this is not a bit - I am an agent of chaos in only the spirit of 100 gecs. The hyper-pop duo of Dylan Brady and Laura Les provide what is likely the most outrageous listen you'll have this...year? Decade? Lifetime? They are the sonic representation of anarchy, and it's impossible not to crack a smile or let out a laugh when experiencing the album existentially. The same formula that produced 2020's 1,000 gecs is at play here, scaled 10 fold: you’re sure to register a visceral reaction of some sort upon pressing play. Perhaps the best summation of 100 gecs as a band worth listening to comes from NYT critic Lindsay Zoladz, who professes that 100 gecs gives smart people the license to be stupid. Outrageous, mind-numbing, sensational, and epiphanous, to embrace the madness is the biggest favor you can do for yourself.

Liv.e, Girl In The Half Pearl

Queuing up Girl In The Half Pearl leads to losing sense of time and place - "I'm too young for the world's big problems / Just let me be free," she pleads to end the opening track. She takes full advantage of this freedom in the tracks to come, asking rhetorical questions with no intent of answering them herself, psychedelically moving through the free-flowing scenes of her mind, perfectly comfortable in the echo chamber of her imagination. Lush and sensual, her flavor of R&B is tart: biting yet surfaceless, cutting-edge ("HowTheyLikeMe!") and slightly jaded ("Wild Animals"). In 17 songs across 41 minutes, Liv.e is exactly what you'd hope: expansive, compelling, and at times daring, a breath of helium-polluted air to a genre ripe with innovation.

Troye Sivan, Something To Give Each Other

Perhaps the unsung pop album of the year, Troye Sivan's Something To Give Each Other boasts a welcome dimensionality, surprisingly as deep as it is wide. The album's pulse certainly suggests life, and Sivan is living it to the fullest - unconstrained euphoria on "Rush," desperation for refunded emotionality on "Still Got It," the unapologetic lust that populates "Got Me Started." The imagery of the album is in it's sound - it's easy to imagine the settings these songs take place in, and where they lead to afterwards. STGEO feels crafted in a way that Sivan's peers wouldn't bother to put in the effort for. A statement piece for Sivan as an artist, it's hard to turn your back on him with how much he has to offer.

Sufjan Stevens, Javelin

Not all albums necessitate context, but in the case of Javelin, it is essential. Dedicated to his partner who passed away in April 2023, there's an emotional weight bearing on each lyric and breath Stevens offers. With this perspective, your heart breaks a million times over across the record, though no moment is quite as shattering as the devastating "Will Anybody Ever Love Me?" One final blow comes in Stevens' cover of "There's A World" to end the album not with a bang but a whimper - an exhausted, sympathetic sigh is the only way to leave in the wake of Javelin. The juxtaposition of strength and weakness is jarring, with Stevens not convinced of security in these songs but wearily searching.

Kara Jackson, Why Does The Earth Give Us People To Love?

And for my last trick, I leave you with the review at The Line of Best Fit, for which Why Does The Earth Give Us People To Love was recognized as the number one album of the year. My words and perspective would only echo those of writer Sophie Leight Walker's, or so I can only hope.

For most artists, seeing their name on global playlists and their face on a billboard is part of the dream. It's almost as if none of it is possible unless first imagining these accomplishments as a distant fantasy. But this was never part of the plan for dee holt, the 19-year-old Quebec-born pop darling whose face illuminated a Spotify ad in her hometown after the release of her debut EP last year, with songs from the project finding their way onto the most popularly curated playlists across the globe. Never did she imagine such a spotlight for herself, she tells me over Zoom, just under 12 hours away from the release of her follow-up EP i’ll be there. “Never,” she repeats whenever reflecting on the position she finds herself in today, incessantly adding a supplementary “ever” to drive home how far-fetched this life seems from the one she had imagined for herself. “I didn't initially want to start doing music. Like it was never, ever in the plans,” holt says. “I never was like, ‘I'm gonna write songs, I'm gonna be an artist.’ It kind of just fell in my lap,” she says with a smile, more of astonishment than of satisfaction. The more we talk, the more it all seems so coincidental to holt, the idea of her having a voice that people actually listen to. “For the past two and a half years, I've still been warming up to the idea that I am like an actual artist,” she offers with a chuckle, tinged with a sense of disbelief that can only be described as genuine.

Being an artist was never fully a foreign concept for holt, who was raised by a mother who is a painter and a father who played several instruments, filling the house with music and introducing holt to all kinds of sounds at a young age. She would often sing (but can’t dance, she freely admits), but became more secluded with her voice as she grew older. Where before she would sing for grandparents, holt had become reserved to the point where she would only sing in the shower. No matter how much she was encouraged by those around her (“Of course your mom’s going to tell you you can sing, right?”), holt bottled up her talents. And when you hide something for so long, it tends to reveal itself in the worst moments. While maybe not the worst scenario imaginable, holt’s moment of truth came when her boyfriend’s family united with her own for the first time, and her mom urged her to perform for the group. “I was like, ‘ah!’” she says with an exclamation that’s almost entirely facial, dropping her jaw nearly out of her Zoom frame and raising her eyebrows almost to the ceiling of the studio she joins me from. After “a lot of convincing,” they came to a compromise: “I sang facing the wall. I sang facing the wall because I couldn't face them.” When she turned around, she was met with teary eyes pasted on stunned faces.

After provoking that type of reaction from those who supported her most, holt felt enabled to imagine what a career as an artist might look like. Still, there were no fantasies of billboards and streams far surpassing 7 figures. Everything seemed immediate, and all too convenient. After the intimate performance in front of her boyfriend’s family, her new biggest fans introduced holt to family friend Benjamin Nadeau, a local producer who holt refers to affectionately as Benji. All of a sudden, things were falling into place in a way that was so convenient it couldn’t be coincidence. Still, holt was skeptical of it all. “It's so strange because as I said before, I never wanted to (pursue music),” she says of the early success she found with her songs. “It was never a plan to release and to try to make my name in music. Like never ever. So the fact that it's kind of happening just while, like…I'm working for it, but in a sense, I'm kind of just laying back and seeing what happens. It makes no sense,” her confusion born out of self-consciousness. It’s as if holt was the last one to be convinced of her merit as an artist. After only her second single, the slinky-sounding “Olivia,” labels were calling. “I think it took me like six months to finally say, ‘okay, yes, let's do this.’ That's how unsure I was,” holt testifies, scrunching her face during conversation as she recalls her thought process while offering complimentary explanations with frenetic hand motions. “But I was like, I'm gonna regret it my entire life if I say no and if I don't go with it, and I'm so, so, so, so, so happy that I did. I love it so much.”

Nowadays, holt undergoes routine reality checks as a product of her seemingly natural-born humility. Not once in our conversation do I get the impression that she’s taking her success for granted, nor does she feel it’s normal. “It's so, so strange to me still,” she says of fans messaging her from China and Europe. When she opens up a playlist to find her name next to Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish, she’ll reflexively think to herself, “what the fuck? How does that make any sense?” Aside from her natural case of imposter syndrome, her family has kept her grounded as her name grows with each release. “I'm not getting used to it at all, but I'm happy that I'm not. I don't ever want to get used to the awe of it and like the ‘oh my God, this is crazy,’ because it's just so surreal. I don't know how else to explain it,” holt says, with an honesty that is unprovoked but much appreciated. After just a short talk with holt, it is clear that the heart she wears on her sleeve when recording extends past the studio.